by Donald Parker, PE, CVS-Life, FSAVE

Part 2. Aesthetics and Worth

“If luxury is the icing on a cake, necessity can be considered the cake itself; and the recipe is design.”

Thus began the introduction to the First Federal Design Assembly, conducted in April 1973 by the Federal Council on the Arts and Humanities. This Assembly devoted itself to examining the necessity of design in visual communications, in architecture, in interiors and in environmental planning. Value Engineering is an important ingredient in the design recipe because it, like design, is an instrument of organization-a medium for persuasion, a means of relating objects to people and a method for improving safety and efficiency. VE is a way to achieve demonstrable design performance.

During this Assembly, the following creed evolved (in part) which provides a sound basis for VE opportunity:

- Design is an urgent requirement, not a cosmetic addition

- Design can be judged for its effectiveness by sound proven criteria

- Design can save money

- Design can save time

- Design enhances communication

- Design simplifies use, simplifies manufacture and simplifies maintenance

Eliminating Frills

In the past, the role of the value engineer and that of the architect has been misunderstood. In one example, a VE suggestion was made to delete a rooftop terrace from a building and substitute a ground level patio to serve the same use by the client.

A construction manager, who was involved, commented that he had already told the design architect that the rooftop terrace should be considered “gingerbread.” The connotations one can draw from such a remark disrupt the objective senses and cause emotions to rise to the defense. But more important, the statement reveals a basic misunderstanding of the architect’s role of interpreting and serving the needs of his client, coupled with a misunderstanding of the VE process to generate alternate solutions for fulfilling those needs.

Somehow, in recent years, the intense need and desire to reduce construction costs has been equated with the act of reducing quality or making sacrifices in requirements down to just above the limit of tolerability. Client, architect and contractor all have been party to reducing costs by chopping away gingerbread and frills, such as the textured coat of paint, or the fountain and pool or the granite entrance, in an effort to meet the budget.

This point of view on VE should not surprise the reader. In his very first text on the subject in 1961, Larry Miles sets forth the following position. “Inherent in the philosophy of value analysis is full retention for the customer of the usefulness and esteem features of the product.” He continues on to state that value work must be done “without reducing in the slightest degree quality, safety, life, reliability, dependability and the features and attractiveness that the customer wants.”

Miles states, that “all cost is for function” and that all a customer wants is a function. He either wants something done or he wants someone pleased. Miles was the first to present both use functions and aesthetic functions in serving the needs of man as part of the value process. Fully understanding this concept will lead one to the conclusion that conditions exist when aesthetics becomes a required function. he trick is to determine, or make a judgment, when an aesthetic function is required, and when it is superfluous.

Defining “Aesthetic”

To do this, one needs to define “aesthetic” to get closer to understanding the problem. Most dictionaries indicate something is aesthetic when it is “sensitive to art and beauty.”

At this point, one must normally exclude fine art from function analysis when it is art produced or intended primarily for beauty alone rather than utility. However, art in the form of drawings, paintings, sculpture and ceramics can be studied when it becomes useful art.

For example, the S.S. Andrea Doria took to the bottom of the sea dozens of fine art originals placed on-board for their use value in attracting passengers to that ship in preference to others. Art has been useful in decorating lobbies of many hotels and corporate headquarters. And who can question the utility of landscape gardening to enhance the pleasantness of a place? Normally it is the useful art-presented in the form of windows, granite, doors and similar items-which contribute to the aesthetic functions under consideration.

Returning to our definition of aesthetics-sensitive to art and beauty-we are ready to define each part and put them back together again in functional form:

SENSITIVITY

This relates either to the senses or to responses of the mind such as:

Senses Mind

See Think

Smell Reflect

Taste Enjoy

Feel Good taste

ART

This is considered to be reflective of creative work or the making or doing of things whose form has beauty.

BEAUTY

This is the quality attributed to whatever pleases or satisfies in certain ways, as in:

Line

Color

Form

Texture

Proportion

Rhythmic Motion

Tone

To illustrate a single application of this definition, consider the functional difference between two products concrete block and brick. Both divide space and support weight. Clearly, the choice between use of these products, normally, would be the aesthetic functions: see color, see form and feel texture.

BRICKWORK

We all know that brick costs more than block. This difference in cost is allocated solely to aesthetic functions; and, when brick is selected, those functions; should be necessary. A case in which they may not be necessary could be when brick is used inside an elevator shaft, because one cannot see it or feel it.

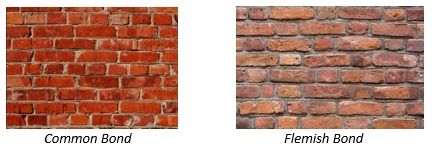

This example of brick shows its sensitivity to beauty. Brick becomes sensitive to art when it reflects creative work, such as in its placing and coursing. The difference in cost between a common bond and a Flemish bond brick wall, for example, is allocated solely to aesthetic function.

FUNCTIONS CAN CHANGE

There is a different point of view in performing function analysis depending upon who you are. Are you a designer or manufacturer of a product or are you a user of a product? What could be basic function to one person might not be basic function to another.

The basic function of a product can change depending on the time and end purpose for which it is used. It is also recognized that products are often purchased (used) for other than their basic function. Buying a screwdriver to open a can of paint is an example of this.

Another example might be the use of a window. Normally, one will use a window to serve the function, view outdoors. Now visualize the same window in a bathroom. Isn’t the glass fogged over? A window in a bathroom may not be there only to provide a view. It is probably there to ventilate the room.

In searching for a proper classification of function, the value analyst can find a clue in the designer’s understanding of why he wants it. If a designer cannot express his need for aesthetic function at the outset, he probably did not consider it essential originally, and more likely than not, the client does not know what it is costing him.

This is a two-edged sword, however, and is useful to the design architect too. Function analysis can be the needed justification to sell a reluctant client on the additional cost of good architecture. It is a system to show exactly what one gets for his money and, as such, responds directly to the needs of the owner. It can show to, that a good design can, at times, be stronger, more attractive, and less costly.

DIFFERENT VALUES

A discussion on aesthetics is not complete without mentioning the different aspects of value. Most value analysts discuss and define three aspects of economic value:

Aspects of Value Relates to

Exchange Value Worth

Esteem Value Want

Use Value Need

VE methodology concentrates on the use value of the “work” or “sell” functions. Carlos Fallon’s book, Value Analysis to Improve Productivity, discusses the nature of value thoroughly. His text is recommended reading for those who deal daily with the value imposed by aesthetics.

Fallon cautions the value analyst who strives to satisfy only needs, while ignoring the desires of man. That is the situation that occurs when one arbitrarily strives to provide only use value and categorizes all aesthetic functions as gingerbread or of doubtful value.

The reference to owners’ desires is a reminder of the over-worked statement, “beauty is in the eye of the beholder.” Paraphrasing this statement, it is also recognized that value is in the eyes of the buyer. Individual desires and concepts of beauty can be the paramount reason something is purchased. Recognize from this, that aesthetics normally is a subjective decision and, very often, an individualistic one. VE is a tool to bring more objectivity to the decisions on aesthetics, usually to gain group acceptance.

Here is a coined definition: esteem value is no more than the desire of the owner to own it. Sometimes an owner does not want it because it does not satisfy his desire (it does not please him aesthetically.) It is important to recognize that elements of esteem can serve a useful purpose; the purpose of making an owner desire it.

Consider then, that aesthetic functions become basic when desire becomes as strong as need.

RELATING VALUE TO WORTH

Like many other English words, value and worth in certain usages commonly may have identical meanings. Miles, in developing and using his techniques used the term “value of a function” as being the lowest cost at which a function could be provided reliably. Others, including the author, believe “worth” is a little better terminology (Miles does not disagree). Miles’ value of a function means the identical of worth of a function as used here.

When elements of utility can be quantified in monetary units, we call them elements of worth so that they can be related to their corresponding elements of cost. In performing VE, we set the precedent of considering:

First, function before cost, second, worth before cost, then, we relate function to worth.

Function worth, by our definition, is the least cost to provide a given function.

The worth of a function is usually determined by comparing the present design for performing the function with other methods of performing essentially the same function. The rule is: determine the cost of a functional equivalent based upon the way it was accomplished previously. To aid in determining worth, one might ask the following series of questions:

- What is the cost of achieving the basic function as the item is presently designed?

- Do you think the performance of the basic function should cost that much?

- If not, what do you consider would be a reasonable amount to pay for the performance of the function (assuming for the moment that the function is actually required) if you were to pay for it out of your own pocket.

- What is the cost of achieving this function if some other known item is used?

- Is this a common, easily accomplished function or one that is rare and difficult to achieve?

- What is the price the some item that will almost but not quite, perform the function?

In determining worth, the key rule to be remembered is that worth is associated with necessary function or functions and not with the present design of the item or system.

To illustrate this, Carlos Fallon related that a task team was trying to define the function of a washing machine hose (cost 25¢) in order to determine its worth. A youngster who happened to be there said, it “bends water!” The team accepted that and sent the boy out to a hardware store to help determine worth by purchasing the cheapest water bender he could find.

The boy came back with a plumbing “U” which at that time cost 5¢. However, the pipe brought back was heavy and ugly. So, the purchasing man on the team called a plastic supplier who, for another 3¢ could make it lighter and softer, and for another 4¢ could make it pretty. The worth of “bending water” thus became 12¢.

Some value specialists give worth only to basic functions, automatically letting the worth of secondary functions be zero. This view is taken because to some, secondary functions only exist because of the design solution used to satisfy the basic functions. Hence, when alternative way to satisfying the basic functions is discovered, all the old secondary functions drop out of existence. The only difficulty with this method is that when a secondary function has cost and its worth is stated as zero, the value index calculation becomes infinity. An index of infinity certainly indicates an area of cost savings opportunity, but is meaningless as an index to rank the areas of cost saving opportunity.

AIDS TO DETERMINING WORTH

Worth can be established at various stages of design or levels of detail. At the component level, one could judge the least cost of the various functions provided by a door. For example, answer the questions:

What is the least cost to…

…seal opening?

…close door?

…lock door?

ALLOCATING COST TO FUNCTION

In the above example, the whole cost of one item was allocated to the cost of one function. Where an item serves but one function, the cost of the item is equal to the cost of the function.

However, in most cases, an item serves more than one function. When this occurs, the cost of the item must be prorated to each function. The next example shows the cost of an acoustical tile suspended ceiling, with a flame spread rating of 25 or less, as 84¢ per square foot and an appropriate breakdown of this cost on a function basis.

To explain how this was done, look at the cost of the mineral tile component. It performs three functions:

Hide structure

Absorb sound

Retard fire

This component has an estimated installed cost of 48¢ per square foot. To allocate this cost to the three functions required a little detective work. First, one can purchase the tile without the flame spread rating function: retard fire” for 43¢ hence, the functional difference in cost is 05¢. If one just wanted to “hide structure” without using perforated tile he could do that function satisfactorily for 30¢. That leaves 18¢ for the “absorb sound” function as its cost.

Where one is in the business of using products rather than manufacturing them, one does not have to be so precise in allocating cost to function. This is not true, however, where large quantities of an item are used and small variances in unit prices add up to large dollar differences. Cost must be as factual and realistic as the sources of information and time to conduct the study will permit.

JUDGING VALUE

With the above information, value can be quantitively expressed through the use of a value index which is the relationship between cost and worth. Remembering that cost and worth are related to functions rather than items, the index serves to:

- Assist in determining whether to proceed with the value study. The study should proceed only if poor value, indicated when the value index is greater than one, exists. Good value is indicated when the index is one.

- Locate areas where the cost/worth ratio is the greatest. Generally, these areas will have the greatest VE potential and are useful items for VE study.

- Provide a factor measuring the effectiveness of any VE efforts. Did the cost/worth ratio approach unity after the VE effort?

Source: Value Engineering Theory by Donald Parker for the Miles Value Foundation © 1977