By Javier Masini, CVS

Very often, Value Engineering professionals talk about the need to distinguish between the cost of unnecessary functions, required functions and secondary functions. As an example, the Society of Japanese Value Engineering’s Guidebook for VE Activities (1981) states that in the VE way of thinking, companies need to cost how much money is spent in unnecessary functions, how much on those secondary required by the customers and how much is actually spent on basic functions.

This makes perfect sense and may seem logical to anyone. But very often, there is confusion between customer needs and customer wants (not even the customer can tell the difference); and there is also the problem for designers assuming they know what the customer expects. For this purpose, many Voice of the Customer tools have been developed and put into practice effectively; some of them are very simple to use and some may not be so simple (or cheap).

In an article published by the Journal of The Japanese Society for Quality Control in April 1984, Professor Noriaki Kano introduced a very simple classification of the elements of quality, wishing quality practitioners would reduce the level of subjectivity in describing what the customer really needs. I’ve found this classification to be very useful when added to the language of functions. Just as it is with the functional approach, when it is a shared language within a team, it makes communication simpler and avoids misunderstandings. This is why, through this article, I wish to introduce the readers to Kano’s classification so you can also share this language within the VE community.

Classification of Quality Elements

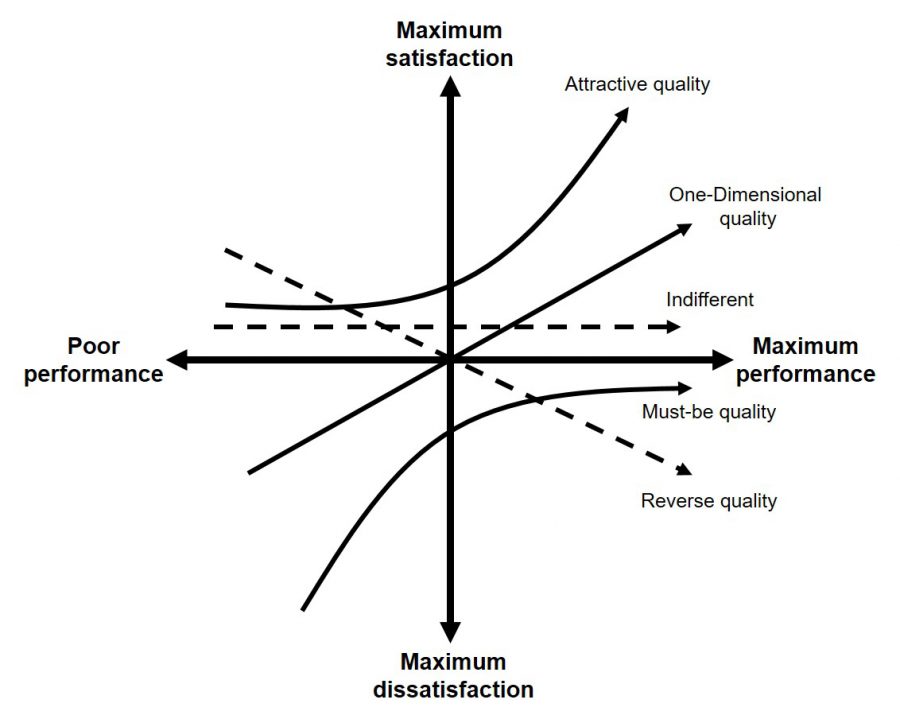

If there is any feature we suspect will have any kind of impact in customer satisfaction, we will call that a “Quality Element” and we know that quality elements can be described as functions. Kano listed these elements to be: must-be quality, one-dimensional quality, attractive quality, indifferent quality and reverse quality.

Figure 1 is constructed using two different axes for two different dimensions. The horizontal axis is a representation of the performance level for a given quality element. Take your car’s mileage per gallon for instance; if your car has a better mileage per gallon, that means you are moving to the right side of the axis while a lower fuel economy means a value towards the left side of the axis. Now the vertical axis is for customer satisfaction, going up means a more satisfied customer while down means dissatisfaction. Now, use those two dimensions to understand each of the elements described next.

Must-be quality: Quality elements that are absolutely expected, even if there is no statement from the customer about it. It does not matter how great its performance can get, there won’t be too much positive impact in customer satisfaction. But, when it does not perform well, creates a huge dissatisfaction. When you ask for a room in your favorite hotel, you never ask for a clean bathroom. If it is incredibly clean, there is not too much impact on your satisfaction. But if it is not clean, you’ll certainly get the phone and will call the front desk. You’ll be disappointed.

One-Dimensional quality: Quality elements that result in satisfaction when fulfilled and dissatisfaction when not fulfilled. Some kind of input about the customer’s expectations are assumed in this type of quality element. In our valued hotel, customers are expected to tell if they want a non-smoking room or not, or deciding between a twin bed or a single king size. The level of satisfaction is proportional to the expected performance. Both satisfaction and performance ranges are as wide as needed.

Attractive quality: Quality elements that when fulfilled provide satisfaction, and it’s acceptable when they are not fulfilled. Sometimes they are called “surprise” or “delight” elements because they are not always expected. If you get free tickets to Liberty Island when you registered in your favorite New York hotel, you’ll get satisfied for certain, it is a nice surprise. Yet, you normally do not expect those tickets, so if you do not get any, you may still feel very satisfied with your service.

Indifferent quality: Quality elements that neither result in satisfaction nor dissatisfaction regardless of whether they are fulfilled or not. If the hotel places a bottle of shampoo that excels in killing bacteria on our scalp, most of us might not even notice it. On the other hand, if it performs poorly on this same element, we might not care about it. So this may be a simple example of an indifferent quality.

Reverse quality: Quality elements that results in dissatisfaction when fulfilled and satisfaction when not fulfilled. Do you receive many phone calls from your bank, favorite airline or hotel? The more they call you, the more dissatisfied you are, don’t you think? For many of us this is an example of a reverse quality element.

This classification is very useful when your design team needs to decide which features need improvement, or what features need to be eliminated from your product. Take the must-be quality elements for instance: there is no need to include any of those expected features in your marketing, for they are expected. And you also do not need to excel on those features either. Your only strategy shall be not to fail on those features, no to excel on them.

Many practitioners believe that many attractive quality elements should be added to delight the customer in a competitive environment. But you need to be careful, they are not expected and they cost money. You should use attractive elements following a planned strategy that do not last long. If an attractive feature is there for long time, it will become expected and now you have increased your cost baseline and customer satisfaction is more complex.

Quality elements are not static; they change trough time. One-dimensional quality elements will become must-be very soon; and some attractive elements may become one-dimensional. This means that knowing what the market expected last decade might not be what it is expected today. Experts in marketing need to update their understanding on what the customer is expecting. Kano introduced a very simple questionnaire to measure and decide what type of quality element a given characteristic is. This questionnaire is out of the scope of this article and will be presented in a later publication.

Figure 1. Kano’s two-dimensional model

It is possible that while reading this article you have already matched the idea of a must-be quality element with Value Engineering’s basic functions; that is totally correct. And you know that the largest cost is not on those functions but in the secondary functions. It is said, for instance, that “unnecessary functions” need to be eliminated. By using Kano’s classification to qualify secondary functions, it will be easier and less subjective to decide what value improvement strategy will fit better to match what the customer expects. Kano’s indifferent functions are those than can easily qualify as unnecessary. One value increasing strategy is to reduce function while reducing cost in a larger amount; this strategy is suitable for must-be functions that have been over-performing, or some attractive functions are also suitable for this same strategy. One-dimensional functions will be at risk if function is reduced, so the strategy here is to increase function while cost remains or is reduced.

The main reason of this article is not to change the classification of functions, but to present Kano’s classification to the Value Engineering community to enrich our common language. I’ve found it very convenient to understand better what the customer needs, and when this language is shared by several team members in a study it makes communication less subjective and more effective to describe the quality of a given function.

References

- Society of Japanese Value Engineering, “Guidebook for VE Activities”, 1981 Translated from 1971’s “VE 活動の手引”.

- Kano, N., Seraku, N., Takahashi, F. and Tsjui, S. “Attractive Quality and Must-be Quality”. (1984) Hinshitsu 14(2), 147–156.